The Ten Commandments and American Law:

Why Some Christians' Claims to Legal Hegemony Are Not Consistent with the Historical Record

|

Let's first address the phrase "hegemonic Christianity." What is this? What form of Christianity enjoys "hegemony" in 21st century secular America? Roy Moore lost his seat on the Alabama Supreme Court because of "hegemonic" Republicans. The Ten Commandments monument was banned from public view. Who has "hegemony?" Certainly not Christians. Certainly not Christians like Elaine Huguenin, who refuse to be enslaved to propagandize for homosexuality and was fined thousands of dollars, or forced

out of business. Clearly, we should be talking about "hegemonic homosexuality," not "hegemonic Christianity."

However, it is a historical fact that in American law, the Ten Commandments once enjoyed legal hegemony over any other source of law, be it Buddhist, Hindu, Moslem, Rabbinic, or the religion of Secular Humanism. That is clearly no longer the case. Hamilton seems to want to argue that it was never the case.

Ten Commandments in U.S. Legal History |

By MARCI HAMILTON

hamilton02@aol.com

---- |

| Thursday, Sep. 11, 2003 |

| When Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore's 2.5-ton sculpture of the Ten Commandments was wheeled out of the courthouse, the furies of hegemonic Christianity were unleashed. Supporters protested, Moore spoke passionately, and commentators echoed the notion that the Ten Commandments are the sole source of American law and therefore never should have been removed. |

The emphasis on "sole" is curious. Where is this emphasis featured in the argument of those who oppose the Stalinist purge of the Ten Commandments from public view?

Analysis of federal decision against Roy Moore and the Ten Commandments. |

| As a Christian, an American, and a scholar, I found the whole thing embarrassing. First, it was such a transparent attempt by Christians to regain power over a country that has become the most pluralistic religious culture in world history. |

Notice she uses the word "regain." The Ten Commandments once enjoyed legal hegemony in America. |

| Second, I was appalled that Americans - including television personalities who have a responsibility to their audience to do their homework - could be so uninformed about the history of our legal system, and its many and diverse sources. |

|

| Third, we proved once more to the world community that as a nation, we have the most abysmal knowledge of history. Worse, this laughable claim about legal history was repeated over and over as plain truth. |

|

| The primary problem with the claim that the Ten Commandments are the sole source of American law is that the facts simply do not support it. To the contrary, there are many, varied sources for American law. At most, some elements of the Ten Commandments play a supporting role. |

|

| The Ten Commandments: Their Text |

|

| It is easy to say American law rests on the Ten Commandments when one selectively remembers their content, but not so easy when one re-reads them. I will use the King James Bible version, since the Protestants who are asserting the right to have the Commandments displayed and promoted by the government would be most familiar with this version. |

|

| They begin: "And God spake all these words, saying," |

|

| 1.Thou shalt have no other gods before me. |

The First Commandment was one of the most frequently cited in America's War for Independence. Toryism was denounced as Idolatry.

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 2.Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth . . . . |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 3.Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 4.Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labour, and do all they work: But the seventh day is the Sabbath of the LORD thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor they maidservant, nor they cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 5.Honour they father and they mother: that they days may be long upon the land which the Lord they God giveth thee. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 6.Thou shalt not kill. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 7.Thou shalt not commit adultery. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 8.Thou shalt not steal. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 9.Thou shalt not bear false witness against they neighbor. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| 10.Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour's. |

How This Commandment was Applied in Early American Law |

| The First Four Commandments: Why They Cannot Constitutionally Be Made Law |

When she says "cannot," she means "must not," because she doesn't want them to be applied. But in fact, they were, and they can again. |

| Even a quick reading of the Ten Commandments demonstrates how strained is the claim that American law derives exclusively from them. |

|

| Early laws in the United States against blasphemy and heresy might be derived from the first three Commandments read together. But those laws long since have been held to be unconstitutional, and rightly so. Were the first three Commandments law, they would bump up against the most important fundamental right in the Constitution: the absolute right to believe whatever one chooses that derives from the First Amendment's Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses. |

"Might be?" What else could they possibly have been derived from? This is not precise and honest analysis.

When is "long since?" In the Larger Catechism, we are asked:

Question 105: What are the sins forbidden in the first commandment?

Answer: The sins forbidden in the first commandment are, atheism, in denying or not having a God . . . .

Atheists were denied access to public office based on this commandment. This was not held "unconstitutional" until 1961. In that case, the Federal Judiciary arrogated to itself the authority to order the Amendment of the Maryland State Constitution. Had Maryland and all other states been informed back in 1787 that the federal Constitution would give the Supreme Court power to order the amendment of state constitutions on the issue of religion, the Constitution would never have been ratified. The First Amendment means absolutely nothing if it doesn't preclude the federal government

from imposing religious views (and especially irreligious views) on the states. |

| James Madison, leader of the Constitutional Convention and drafter of the First Amendment, explained it as follows: "The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate." |

In his Memorial and Remonstrance, Madison articulated the view that our civil society was based on the First Commandment: "Before any man can be considered as a member of Civil Society, he must be considered as a subject of the Governor of the Universe." Those who violated the First Commandment were therefore banned from public office, and could not obtain citizenship in most states.

In the next sentence after the one Hamilton quotes, Madison said,

It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator ... homage.... This duty is predecent both in order of time and degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.

The Civil Magistrate, then, must not discriminate between the manner of rendering homage to the Creator as understood by Quakers and Presbyterians, but it can discriminate between those who render homage according to their conviction and conscience, and those who believe they themselves are gods. The latter should not be given the reins of political power.

Madison, the "Father of the Constitution," said that legislators should vote against any legislation if

the policy of the bill is adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity. The first wish of those who enjoy this precious gift, ought to be that it may be imparted to the whole race of mankind. Compare the number of those who have as yet received it with the number still remaining under the dominion of false religions; and how small is the former! Does the policy of the Bill tend to lessen the disproportion? No; it at once discourages those who are strangers to the light of (revelation) from coming into the Region of it; and countenances, by example the nations

who continue in darkness, in shutting out those who might convey it to them. Instead of levelling as far as possible, every obstacle to the victorious progress of truth, the Bill with an ignoble and unchristian timidity would circumscribe it, with a wall of defence, against the encroachments of error.

Adherents of any "false religion" are free to believe anything they want between their two ears, but America's Founders agreed that they did not have the freedom to openly and publicly violate the Ten Commandments. |

| The Supreme Court, in a widely admired opinion, West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, affirmed the same principle. There, it memorably declared: "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion . . . ." The Barnette rule captures what is best, and even miraculous, about American constitutionalism--its strong and broad support for a meaningful freedom of conscience to believe whatever moves

one's soul. |

In this 1943 case, Jehovah's Witnesses were told they did not have to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. In 1943, Christianity still retained some "hegemony." But toward the end of the century, Courts ruled that NOBODY could recite the Pledge with the words "under God" in it, because atheists complained about having to recite those two words. The atheists should have been told that they don't have to recite those two words, citing the Barnette case. Instead, NOBODY was allowed to say those words. End of Christian hegemony. |

| Thus, were the first four commandments enacted into law today, they would constitute plain constitutional violations. It is an exceedingly strange, and strained, argument that argues the primacy of the Ten Commandments as the true American source of law when the first four simply cannot be enacted into law, because they would conflict with our Constitution. The first four prove that the Commandments are religious rules, not civil law. So as a starting point, only the latter six could possibly be nominees as possible sources of our governing laws. |

Not a single person who signed the Constitution in 1787 would agree with Hamilton's conclusion. Not one. Not a single Signer would agree with recent court decisions which are anti-Christian and pro-atheist, and reflect declining Christian hegemony, if not a war against Christianity. |

| The Latter Six Commandments: Hardly the Sole Source of American Law |

|

| Moreover, two of the remaining six can be immediately ruled out. Number Five--honor one's mother and father--is not a legal rule, but rather a moral imperative. So is Number Seven, the prohibition on cheating on one's spouse. |

The most radical forms of dishonoring parents are still punishable at law. They are called "elder abuse." And there are a few laws still remaining which require parental consent from a minor who would join the military, get married, drive a car, incur debts, spend an inheritance, or get a job. (But not if the minor child wants to murder her illegitimate child; that's now a "fundamental right.")

The more positive forms of honor, such as standing when an adult enters the room, used to be common place in public schools. Today's teachers fear armed students. |

| Of course, in modern times, adultery is legally relevant as a ground for divorce. But allowing adultery to be such a ground is hardly the same as incorporating a direct prohibition against adultery into law. To the contrary, if tested by the Supreme Court, a direct criminal prohibition against adultery would likely be struck down as unconstitutional, whereas the Court would have no problem in recognizing adultery as a factor towards dissolving a union that was based on fidelity. |

Adultery used to be a crime. Hamilton is certainly permitted to say "I don't think it should have been." But she should not say "It never was." Hamilton is entitled to her own opinion, but not her own historical facts. Nearly two hundred years of legal history under the Constitution went by before people like Hamilton began finding laws against adultery in the military "unconstitutional." It is a relatively recent trend, unimaginable to America's Founders. |

| Similarly, the Tenth Commandment's ban on coveting - including coveting thy neighbor's wife - might play a role in a divorce proceeding, but not in a criminal case. Indeed, under the First Amendment, we are generally free to want what we like, and say that we want it, as long as we do not illegally take it, or - if what we covet is a person - resort to stalking or sexual harassment. |

Nobody advocates thought crimes -- oh, wait, Hamilton does. |

| That leaves the prohibitions in Commandments Six, Eight, and Nine: They command us not to kill, steal, or lie. Even these are not reflected in our law in their entirety. |

|

| Granted, the ban on lying does appear as a legal rule in some contexts - for instance, a misrepresentation can be the basis for fraud. But many lies are not legally regulated. Thus, perjury is illegal, but telling your best friend you love her new, disastrous hairdo is not. |

Hamilton is a liar, a dissembler, and a deceiver.

It is time that the citizens of this state [California] fully realized that the Biblical injunction "Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour," has been incorporated into the law of this state, and that every person before any competent tribunal, officer, or person, in any of the cases in which such an oath may by law be administered, wilfully and contrary to such oath, states as true any material matter which he knows to be false, is guilty of perjury, and is punishable by imprisonment in the state prison for not less than one nor more than fourteen years.

People v. Rosen, 20 Cal.App.2d 445, 66 P.2d 1208, 1210 (1937)(J.McComb)

|

| In the civil context, a lie that does not cause damage (and fulfill other requirements as well) cannot be the basis for a tort suit. In the criminal context, not all lies are perjury: Only lies under oath; lies to the government are also criminalized, but only in some circumstances. |

In his Farewell Address, Washington said:

Let it simply be asked, Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

Stephen Epstein, a staunch opponent of the Religious Right, writes in the Colombia Law Review:

It is, therefore, not surprising that the South Carolina Supreme Court is reported to have noted in 1848 that

"[i]n the courts over which we preside, we daily acknowledge Christianity as the most solemn part of our administration. A Christian witness, having no religious scruples against placing his hand upon the Book, is sworn upon the holy Evangelists -- the books of the New Testament, which testify of our Savior's birth, life, death and resurrection; this is so common a matter that it is little thought of as an evidence of the part which Christianity has in the common law."[168]

It would be very difficult to find one Founding Father, or any other legal authority, writing before, say 1960, who would not acknowledge that the Ninth Commandment was a foundation of America's legal system. |

| That leaves us with only two commandments that are somewhat accurately echoed in current law: the rule against murder, and the rule against stealing. And even the rule against murder is not exactly the same as the Commandment: We recognize exceptions, such as self-defense, that the Commandment simply does not. |

John Locke would be appalled at a so-called legal expert who claims that the Bible does not allow for self-defense, and that, therefore, the Sixth Commandment cannot be the basis for our nation's law.

Hamilton is correct to claim that the Eighth Commandment against theft is not honored in any meaningful way by today's politicians. |

| Moreover, it is impossible to attribute the continuing force of these laws solely to their Ten Commandments' origin. And that origin is not unique: There is no civilized country that has not settled upon these two principles. |

There is no civilized country that has not settled on these principles because the Bible required it. |

| In any event, focus on the Commandments themselves also leads one to forget the enormous complexity of American law. The laws controlling shareholders or the environment can only be attributed to the most labyrinthine reasoning. |

|

| A Quick Tour Through the Historical Record |

|

| The claim that the Ten Commandments are the foundational source of American law defies history. Of course, there is simply no way to cover the many sources of the many aspects of American law in a column (or even in a book or encyclopedia). In fact, the sources are legion and cannot be traced back to any single origin or tradition. Here is a quick tour, an introduction. |

Which is to say that no column, book, or encyclopedia has ever documented the non-Christian sources of American law. How convenient. But in the right-hand column of this webpage we've seen plenty of evidence that the Ten Commandments (and the rest of Biblical Law) were in fact the foundation of American law.

The law given from Sinai was a civil and municipal as well as a moral and religious code. . . Vain indeed would be the search among the writings of profane antiquity . . . to find so broad, so complete, and so solid a basis for morality as this decalogue lays down.

John Quincy Adams, Letters of JQA to His Son on the Bible and its Teachings, (1850), pp. 70-71

|

| The written law was founded first--to the best of anyone's knowledge--in the Code of Hammurabi, the sixth ruler of the First Dynasty of Babylon, who ruled from 1792-1750 B.C.. Hammurabi's code was lengthy and detailed, though not comprehensive. While an actual copy of the Code itself did not appear in modern times until an excavation in 1902, the existence of such a code was known before then and is considered by scholars to be the precursor in important respects to Jewish or Hebrew law. Indeed, the Ten Commandments echo some of the rules that appear in Hammurabi's Code. |

Abraham pre-dated Hammurabi. It is said of Abraham:

Abraham shall surely become a great and mighty nation, and all the nations of the earth shall be blessed in him. For I know him, that he will command his children and his household after him, and they shall keep the way of the LORD, to do justice and judgment; that the LORD may bring upon Abraham that which He hath spoken of him.

Genesis 18:18-19

Therefore God blessed Abraham for his obedience to God's commandments.

"Abraham was very rich in cattle, in silver, and in gold" (Genesis 13:2).

"The LORD has blessed my master greatly, and he has become great; and He has given him flocks and herds, silver and gold, male and female servants, and camels and donkeys. (Genesis 24:35)

Because that Abraham obeyed My Voice, and kept My Charge, My Commandments, My Statutes, and My Laws.

Genesis 26:5

These commandments, statutes, and laws were essentially those that were cast in stone and codified by Moses, and they predated Hammurabi. |

| Roughly one thousand years later, the Ten Commandments appeared. |

So, according to Hamilton, the Bible is lying when it says God gave the Ten Commandments to Moses any time before c. 750 B.C. This is just propaganda. It is an implicit claim that the Bible is a complete fraud. Isaiah the prophet lived around 750 B.C. He evidently lied when he spoke of Moses living "in days of old," as did David, other kings, and other prophets. |

| Interestingly, over the centuries, many Christians have claimed that the Ten Commandments did not govern their conduct, because they were given dispensation from the Commandments through Christ--a claim that severely undermines the notion that the Ten Commandments were always considered by Christians to be the supreme and foundational law. Others have embraced the Ten Commandments as part of the history of Christianity. Now some claim that they are the sole source of the secular law that binds everyone in secular law. Such turnarounds are not uncommon in history, but they are impossible to know if one does not know any history! |

"Over the centuries," these people, like Marcion, were considered heretics. The mainstream of Christendom has considered the Ten Commandments to be the foundation of public law and social order since the fall of Rome.

- JSTOR: Reviewing An Introduction to Early English Law: The Law-Codes of Ethelbert of Kent, Alfred the Great, and the Short Codes from the Reigns of Edmund and Ethelred the Unready by Bill Griffiths. Law and History Review, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Spring, 1998), pp. 174-175:

"Ethelbert's code of about 600 C.E. begins with penalties against stealing church ... It begins with the Ten Commandments, limits slavery to seven years . . . " etc.

- Alfred the Great; Christian History Institute

|

| The Magna Carta, which forced the British King John to give up many rights to the aristocracy, was first set down in 1215 A.D. It was the first declaration that the people's ruler was under the law, the first check on royal power, and it introduced nascent concepts of due process, jury by one's peers, freedom of religion, and no taxation without representation. |

More on the Magna Carta. |

| Other monarchs agreed to future Magna Cartas, and it came to be considered central to the law of England. Even though it took a back seat during the 1500s, it was re-discovered and embraced in the 1600s to fight the tyranny of the Stuarts. Parliament used it as a wedge against the monarchs, in effect, creating the beginnings of the separation of powers we now take for granted. It is common knowledge that the principles of the Magna Carta were carried across the Atlantic to the New World and the colonies, and bore fruit in the United States Constitution and state laws. |

|

| The most recent copy was recently installed with much pomp and circumstance in a handsome display in Philadelphia's Independence Visitors' Center. There is no question that the Magna Carta--which was the first written declaration of rights by landowners against the monarchy--was a strong influence on later rights declarations, including the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. |

|

| The vast majority of American law, including the rules against killing and stealing, was borrowed in whole or in part from the British common law--which itself was viewed either as rising from natural law or from custom, not from the Ten Commandments. |

Disconnecting the Common Law from the Ten Commandments is poor scholarship.

One of the beautiful boasts of our municipal jurisprudence is that Christianity is part of the Common Law. . . . There never has been a period in which the Common Law did not recognize Christianity as lying at its foundations. . . . I verily believe Christianity necessary to the support of civil society.

-- US Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story,

Founder of Harvard Law School

|

| The Founders and the Framers Adamantly Did Not Intend to Make the Ten Commandments Law |

|

| Thomas Jefferson specifically railed against attempts to claim that the common law incorporated the Ten Commandments when he criticized judges for "lay[ing] the yoke of their own opinions on the necks of others by declaring that [the Ten Commandments] make a part of the law of the land." John Adams also questioned the influence of the Commandments and the Sermon on the Mount on the legal system. |

Jefferson was wildly in the minority on this point. He was grinding an ax, and his argument was just plain wrong. Adams is frequently mis-quoted by internet infidels. I would like to see the original John Adams source to read it in context.

Conclude not from all this, that I have renounced the Christian religion, or that I agree with Dupuis in all his Sentiments. Far from it. I see in every Page, Something to recommend Christianity in its Purity and Something to discredit its Corruptions. ...The Ten Commandments and the Sermon on the Mount contain my Religion."

- John Adams, Letter to Thomas Jefferson, November 4, 1816

Read more

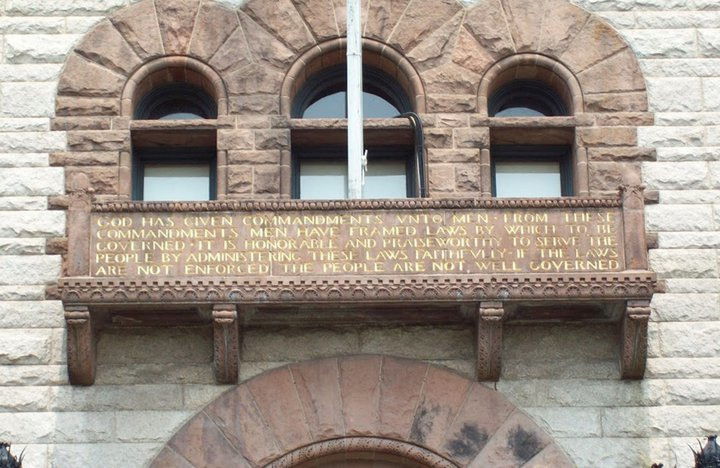

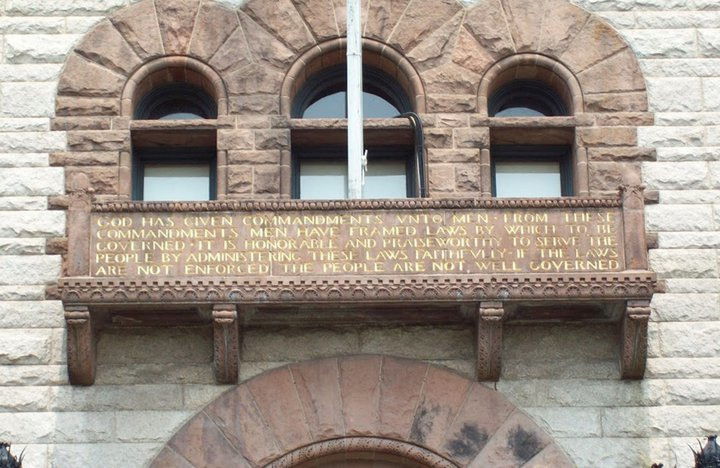

“God has given Commandments unto Men. From these Commandments Men have framed Laws by which to be governed. It is honorable and praiseworthy to serve the people administering these Laws faithfully. If the Laws are not enforced, the People are not well governed.”

Inscription over the front door of the City Hall of Cambridge, Massachusetts (A.D. 1888)

|

| At the Constitutional Convention, the Framers looked to the examples of antiquity--the Greeks and the Romans - and not to the Ten Commandments. They were a pragmatic lot, and they were not interested in being bound by their religious heritage (despite today's claims to the contrary). Rather, they were searching for virtually any idea--from virtually any source--that would work to create a better government than the failure produced by the Articles of Confederation. |

The question on the floor at the Constitutional Convention was not the Ten Commandments and its bearing on crimes of murder, theft, perjury, adultery, etc. The Constitution is procedural, not substantive law.

Hamilton again unwittingly admits that the Ten Commandments were part of the Framers' "religious heritage." They would protest her characterization of them as secularists without religious foundations.

|

| Those Framers who were well educated had studied antiquity and the classics in depth (unlike the vast majority of Americans today, even those who are college educated). Thus, they were perfectly comfortable borrowing and adapting whatever suited their purposes. It would be a huge overstatement to say that they felt themselves constrained by the four corners of the Bible in finding the right government, or setting up the ultimate law that would rule the U.S. |

The Framers rejected antiquity more than they adopted it. As Constitutional historian Clinton Rossiter notes, even when they mentioned Rome,

The Roman example worked both ways: From the decline of the republic Americans could learn the fate of free states that succumb to luxury.

Alexander Hamilton wrote that it would be “as ridiculous to seek for [political] models in the simple ages of Greece and Rome as it would be to go in quest of them among the Hottentots and Laplanders.”

In The Federalist Papers, we read at one point that the classical idea of liberty decreed “to the same citizens the hemlock on one day and statues on the next….” And elsewhere: “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.”

Dinesh D'Sousa writes:

In ancient Greece and Rome, individual human life had no particular value in and of itself. The Spartans left weak children to die on the hillside. Infanticide was common, as it is common even today in many parts of the world. Fathers who wanted sons had few qualms about drowning their newborn daughters. Human beings were routinely bludgeoned to death or mauled by wild animals in the Roman gladiatorial arena. Many of the great classical thinkers saw nothing wrong with these practices. Christianity, on the other hand, contributed to their demise by fostering moral outrage at the mistreatment of innocent human life.

The Ten Commandments was not a blueprint for political procedure (constitutions, confederacies, etc.), but it was for substantive moral law, which America adopted, rather than the morality of Rome. |

| The sources that influenced the Framers ranged from Greek and Roman law, to John Locke, to Scottish Common Sense philosophers, to Grotius. The influence of the Common Sensists was quite evident in the Framers' strong belief in the power of reason--not revelation or Biblical passages--to determine government. They were also influenced by the dominant religion of the time--Calvinism--in the sense that their world view was rooted in distrust of any human who holds power. And this list is only a beginning. |

John Locke was a Christian Theocrat who wrote a constitution for Carolina that excluded atheists from public office. His treatise on government was a commentary on the Bible, beginning in the Garden of Eden ("state of nature").

Reason and the Bible are not in conflict. If the world is a random, meaningless, evolving blog, there is no reason.

America was basically a Calvinist nation. Calvin was a Bible-junkie.

|

| Meanwhile, the very tenor of the times was distrustful of organized religion, and especially stakeholder claims to truth by religious individuals. Madison declared, in his Memorial and Remonstrance of 1785, "experience witnesseth that ecclesiastical establishments, instead of maintaining purity and efficacy of Religion, have had a contrary operation. During almost fifteen centuries, the legal establishment of Christianity has been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution." |

I am not a member of any institutional church, and distrust ecclesiastical archists. There are no ecclesiastical denominations in the Bible or the Ten Commandments.

As a Christian and a libertarian, I am much closer to Madison than the policy prescriptions of Marci Hamilton.

|

| And when Benjamin Franklin presented the draft Constitution to the Congress, he declared: "Most men indeed as well as most sects in Religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from that it is so far error. Steele[,] a Protestant[,] in a Dedication tells the Pope, that the only difference between our Churches in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrines is, the Church of Rome is infallible and the Church of England is never in the wrong. But though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as to that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who in a dispute with her sister, said

"I don't know how it happens, Sister but I meet with no body but myself, that's always in the right . . . ." |

More on Franklin.

This has nothing whatsoever to do with the debate over the Ten Commandments. Franklin and these churches agreed on the Ten Commandments, despite whatever other conflicts they had over superficial ecclesiastical dogmas.

|

| Why the Pro-Ten-Commandments Statue Forces Are Misguided |

|

| Were Franklin speaking today, one might be mightily suspicious he was speaking of Justice Moore, who placed a plaque on his Ten Commandments monument that said "Laws Of Nature And Of Nature's God." |

Blackstone said that the "Laws Of Nature And Of Nature's God" could only be found in the Holy Scriptures. |

| No rational Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, atheist, or agnostic--each of whom's beliefs are equally and fully constitutionally protected--could rationally expect justice in those halls. As Madison warned, "Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects?" |

Madison is taken out of context. Madison would never have agreed to the proposition that we cannot "establish Christianity" in the sense of prohibiting adherents of the religion of the Incas and the Mayans from sacrificing their children to the sun-god, in violation of the Sixth Commandment. Madison would say that Christianity was established rather than other "false religions." |

| It is important to distinguish the public square from public buildings. Christians have been making the argument at least since Stephen Carter published The Culture of Disbelief in 1993 that they have been pushed out of the public square. What this current debate shows is that they have been prohibited from using public buildings or settings for their religious messages, not from speaking in the public square. |

Public buildings and monuments in Washington D.C., are replete with references to Christianity and the Ten Commandments, but not to Buddhism, Islam, or the Incas. |

| Christians have no shortage of access to the public square, which is where free speech and public debate take place. The Constitution strongly and equally protects their free exercise of religion, and their right not to have any religion established as part of our federal or state governments. And there are numerous legitimate and effective places for that very free exercise and free speech, other than a courthouse designed to offer justice to all, irrespective of race, creed, or religion. That is what a town square or a public park is all about. |

A Jew has a better chance for justice in a Christian nation than in an Islamic nation. An atheist has a better chance for justice in a Christian nation than in an atheistic nation like the "former" Soviet Union. A Moslem has a better chance for justice in a Christian nation than in a Moslem nation. This is why Moslems immigrate to America, but Christians don't immigrate to Islamic nations. |

| If Justice Moore (in his private and plainclothes capacity, without his judicial robes and title) mounted his 10 Commandments statue on wheels today and wheeled it around the country, he'd have 24/7 coverage and apparently plenty of people trailing along. All citizens have the right to proselytize, preach, and promote their religion to their hearts' content. What they do not have is the right to use the government's might and power in the service of their beliefs. |

The original purpose of government in America was to promote Christianity. |

| Nevertheless, the drive in Alabama to get the Ten Commandments into a government building, as opposed to the public square, continues. Alabama's Governor Riley on Tuesday announced a "historical display in the old Supreme Court library" of the State Capitol. The collection includes the Ten Commandments, the Magna Carta, the Mayflower Compact, and the Declaration of Independence. |

Public school teachers, under the atheistic reign of Hamilton and her ilk, are prohibited from teaching public school students that the Declaration of Independence is really, objectively true. Any conservative Christian who gained traction in a move to have the Declaration of Independence promoted in public schools would be denounced by Hamilton as one attempting to "impose a theocracy" on America. |

| Attorney General Bill Pryor assisted the Governor, saying that he hoped that "Alabamians will visit our State Capitol to learn more about the development of the rule of law." There is also an "accompanying book with the texts of these legal documents." |

|

| This is a step in the right direction, to be sure - a step towards acknowledging the many and diverse sources of American law. Still, the display emphasizes the narrowness of Americans' historical horizons. When it comes to legal and religious history, Americans have proven themselves to be woefully ignorant. How else could such untruth about the Ten Commandments' status as an influence on our law be so widely and uncritically repeated and accepted? |

The very chamber in which oral arguments on this case were heard is decorated with a notable and permanent - not seasonal - symbol of religion: Moses with the Ten Commandments.

There are countless other illustrations of the Government's acknowledgment of our religious heritage and governmental sponsorship of

graphic manifestations of that heritage.

Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S. 668, 677, 1984

The Ten Commandments & Their Influence on American Law - A Study in History |

|

|

|

Ten Commandments in the U.S. Supreme Court Building

|